After almost 2 years of being back in Oman, I finally visited the Ras Al Jinz Turtle Reserve. The reserve was established in 1996 to protect 45 km of Oman’s Eastern shore and conserve the nesting ground of sea turtles. The Ras Al Jinz beach is world famous for the nesting of the endangered green turtle (Chelonia mydas) and probably is the most important nesting concentration on the Indian Ocean. It is also the only official place where the public can visit and watch this unique experience.

Ras Al Jinz is part of the Ras Al Hadd coastline, an area of rugged beauty, with rocky cliffs overlooking the azure waters of the ocean. As the easternmost point in the Arabian Peninsula, it is the first location to see the rising sun every morning. The last time I visited the reserve was in 2004 when driving from Muscat required a 4WD vehicle to negotiate the gravel road from Quriyat to Ras Al Jinz. Today, a modern 250 km long dual carriage way connects Muscat to Sur (route 17), and from there to Ras Al Jinz is only another 50 km or so along a black top road. Of course, this means that a lot has changed in the intervening years, with more people visiting the reserve.

There are many interesting stops along the way, like the Bimah sinkhole, a collapsed cave that has a beautiful lake; several nice beaches along the coast between Tiwi and Fins, with white sand and warm sea water; Wadi Shab, for a great wadi trekking along several pools; and the archaeological site in Qalhat, just to name a few. Thus, I recommend allowing extra time to check these places. Without stopping, it takes roughly 3 hours from Muscat to Sur.

The best time to see the turtles in during the months of July and August, when hundreds of turtles arrive after sunset to lay their eggs. Even though the summer is hot in Oman, this coastline is buffeted by strong winds during the monsoon season, which reduces the temperature. There are two guided visits daily, one at 9 pm, and one at 5 am.

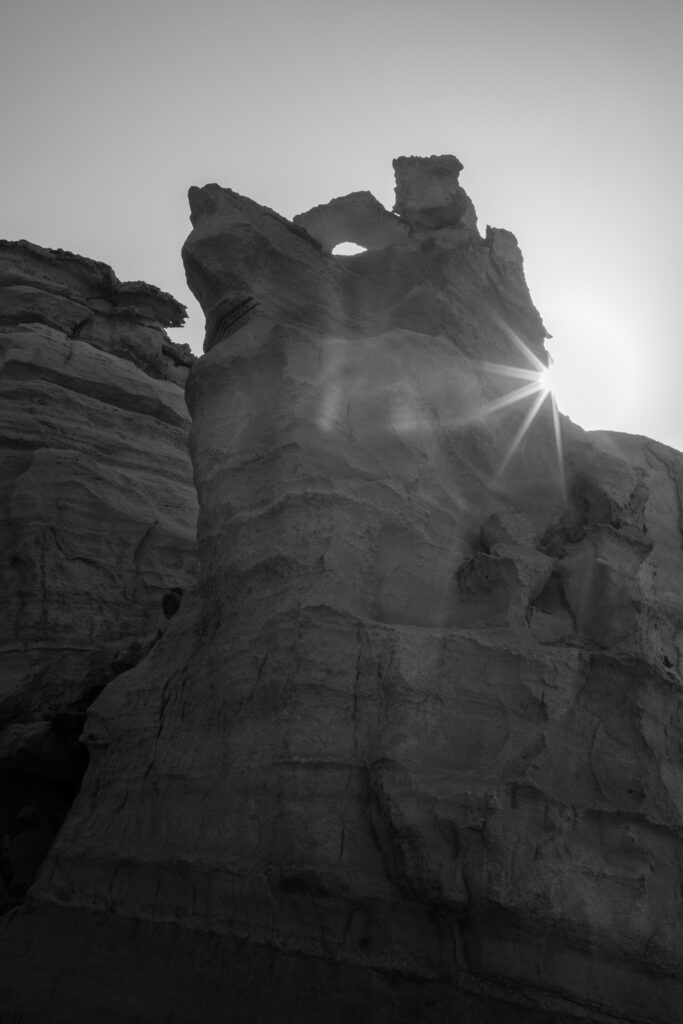

There are several choices for accommodation near the reserve, we decided to stay in the Ras Al Jins Reserve hotel, where the visitor centre is located. This was more convenient, as it makes logistics easier. After arriving at the hotel, we rested for a while and then walked the 1 km or so to the beach. The area is characterized by dry and rocky coastal plain, where eroded limestone and sandstone cliffs rise above the landscape. The wind was really blowing strong, picking up dust and sand; the sea was quite rough as well.

It is possible to stay in the beach until 5.30 pm, when it closes to the public, so I walked around taking some photos and remembering the previous visit from 20 years ago. It was impossible not to notice the large number of “craters” in the sand, where the turtles had excavated their nests. Egg shells were also conspicuous. I made several photos of the beach and its surrounding rocky outcrops, which have been sculpted by wind and water for millennia. The whole Ras Al Hadd peninsula was also home to pre-historic human settlements dating to 5,000 – 3,000 years ago, when the climate was less dry. Several signs describe these archaeological sites, dispersed along the region.

As the sunset was approaching, I returned to the hotel for an early dinner, and to be ready for the night visit. The visitor centre was busy, with maybe 50 to 60 people waiting; the guides separated us into groups, and off we went on a minibus to the beach. The night was beautiful and clear under the light of full moon. We were given a series of instructions to avoid disturbing the turtles and waited until our guide would waive us to see one of them in the nest. These turtles reach maturity at 25 years of age and can live up to 80 years old; they return to the beach where they were born to lay their eggs, hence starting the next cycle. It is truly a magical and humble experience to watch them arriving from the sea after swimming thousands of km and start climbing up the sand to dig up their nest. They arrive exhausted and still take around 3 hours to lay their eggs, in an impressive effort. Then they exit the nest and return to the ocean.

Photographically speaking, of course no flash is permitted. The guide has a flashlight with a red colored bulb to help observation, and in general people are well behaved and follow instructions. I had a 27mm f/2 lens on my Fuji camera and with the full moon I was able to use apertures between f/2 and f/4 with ISO around 3200. Later at home, I decided to convert the Raw files to black and white to get rid of the intense red color cast.

Upon arriving at the beach for the morning visit, the sand was full of tracks, many from the turtles climbing the up the sand; but also, numerous ones from foxes, who prey on the eggs buried in the sand. Abundant eggshells provide testimony of the baby turtles hatching; their journey is a daunting one because as soon as they hatch, they must climb out of the crater and negotiate their way to the water. The distance is small for us, but it is big for them, and they also must survive the sea birds and crabs. About 1 in 500 baby turtles make it to safety, which is a clear indication of the risks these animals face since the day they are born.

Even with more visitors, the Ras Al Jinz Turtle Reserve still provides a unique experience, one to be enjoyed with respect for these wonderful animals.

I would like to end this piece with a photo from 21 years ago. Same place, same magic.